What Do You Believe That You’ve Never Researched?

What comes to mind when you hear someone say, "Black people commit the most crime in America"? Does your body tense? Do you nod in agreement? Do you pause to think? Or do you simply accept it as fact because you've heard it so many times, repeated across various platforms, from dinner table conversations to news headlines and even political rhetoric?

Let me be clear: this reflection isn’t about proving anyone wrong. It’s not an academic exercise in defending identity. It’s a plea, especially to practitioners, to policymakers, to those who hold community and public trust, to pause and examine what we repeat as truth. It’s an invitation to critical self-reflection, urging us to recognize the deep roots of our beliefs and the responsibility that comes with sharing information in a public sphere.

Because data has power. And when weaponized, it has consequence. Misinformation, particularly when cloaked in the guise of statistical truth, can erode trust, deepen divides, and perpetuate systemic inequalities.

The Need for Ethical Data, and the Danger of Its Absence

Attacking violence, whether through public health, policing, or prevention, comes with a myriad of theories, ideologies, and frameworks. However, if there’s one thing we should all agree on, it’s the necessity of ethical and accurate data, as well as the responsibility to question the narratives built around it. Without this foundational commitment to truth, even well-intentioned efforts can inadvertently cause harm, reinforcing the very biases we aim to dismantle.

The Myth vs. The Metrics

According to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program:

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2019). Table 43

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2019). Table 43: Arrests by race and ethnicity, 2019. Crime in the United States 2019. U.S. Department of Justice. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/topic-pages/tables/table-43

In 2019:

69.4% of people arrested were White

26.6% were Black or African American

And according to the FBI UCR 2023 dataset:

White individuals accounted for approximately 64.15% of the arrests.

Black or African American individuals accounted for approximately 28.84% of the arrests.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2023). Crime Data Explorer: Arrests by race. U.S. Department of Justice.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2023). Crime Data Explorer: Arrests by race. U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/arrest

These consistent trends across years demonstrate that the majority of arrests in the United States are of white individuals. And yet the public imagination, the one shaped by media coverage, cherry-picked statistics, and generational bias, continues to paint Black communities as inherently criminal. This persistent misrepresentation isn't merely an inconvenience; it's a profound distortion of reality that underpins harmful stereotypes and shapes public perception in ways that are deeply inequitable.

These narratives don’t emerge in a vacuum. They are shaped by decades of selective storytelling and sustained by confirmation bias. Once false narratives are implanted, they require no evidence, just repetition.

Confirmation bias is powerful because it’s invisible. We rarely notice it until someone holds up a mirror. It filters the information we accept, highlights what aligns with our beliefs, and discards what doesn’t. And when entire systems operate under its influence, bias becomes baked into the bones of policy. We see it in sentencing disparities, stop-and-frisk patterns, school discipline rates, and which neighborhoods are deemed ‘high-risk’ without question.

And that unchecked repetition? It has consequences. Beyond individual perception, it influences the very fabric of our society, impacting everything from individual interactions to institutional practices.

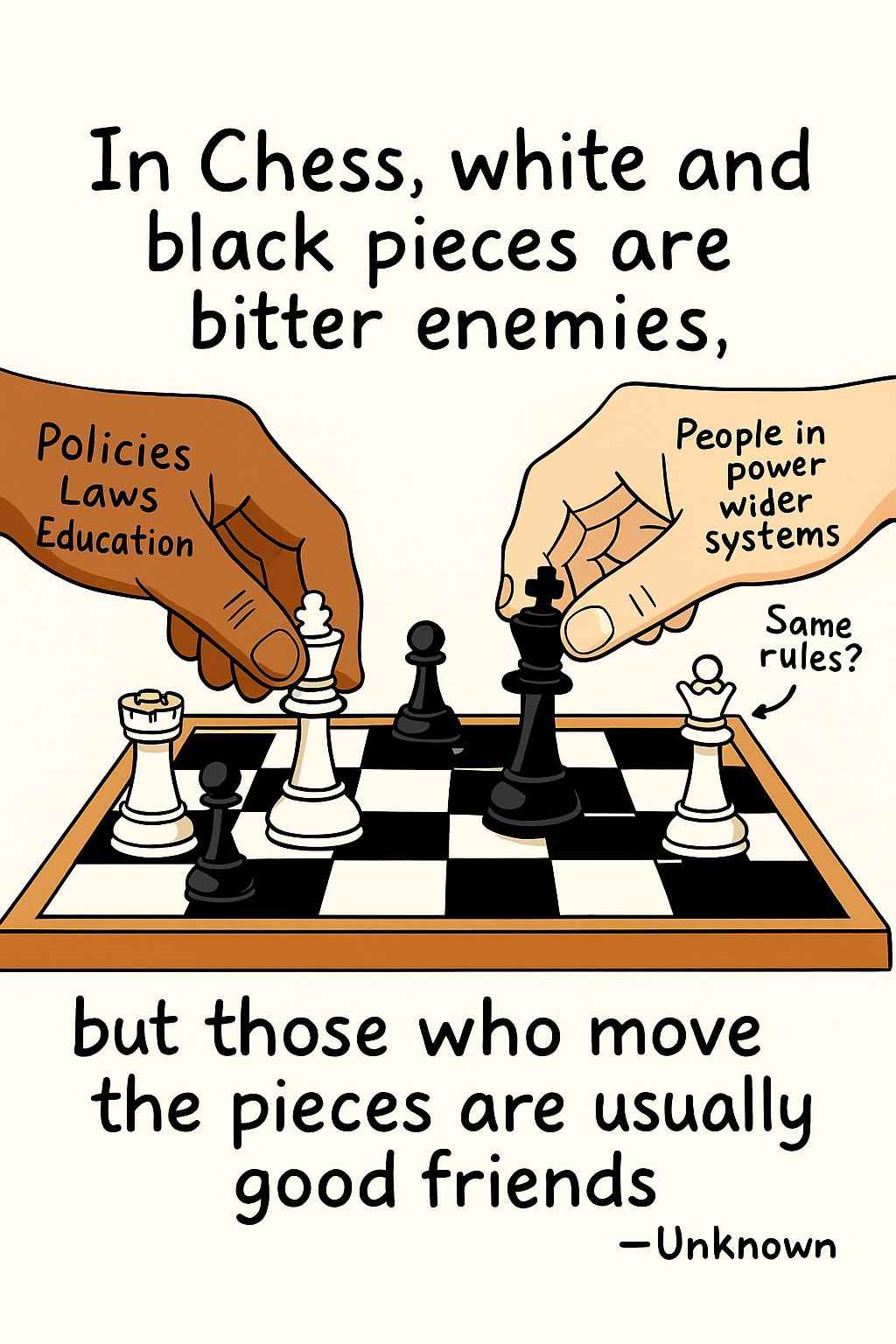

Before we talk about policy, let’s pause for a moment on perception, on how we’re conditioned to see conflict. The quote below, illustrated by Heidi Pickett, captures a subtle but profound truth: that the perceived enemies in a system are often moved by hands that remain invisible, and too often, unaccountable.

Seeing the Game Beyond the Pieces

“In Chess, white and black pieces are bitter enemies, but those who move the pieces are usually good friends.”

— Unknown

Original concept by Heidi Pickett. Illustration adapted and edited.

This visual reminds us: systemic inequality isn’t always loud. It doesn’t just show up in courtrooms or prisons. It influences algorithms, funding decisions, hiring practices, and how we discuss crime, race, and responsibility. It urges us to ask: who’s really moving the pieces?

When False Narratives Become Policy

When bias informs perception, perception becomes policy. We over-police communities that are already vulnerable. We justify surveillance. We fund systems that harm under the guise of protecting. We teach children through practice, not curriculum, that who they are is synonymous with risk. This isn't an abstract concept; it translates directly into disproportionate arrests for minor offenses, harsher sentencing, and a cycle of incarceration that devastates families and communities.

The Innocence Project reports that nearly 60% of those exonerated since 1992 have been Black, despite Black Americans making up just 13.6% of the U.S. population. Worse still, a 2022 study found that innocent Black individuals are seven times more likely to be wrongly convicted of murder than their white counterparts. These stark disparities are a chilling testament to how ingrained biases, often fueled by false narratives, can compromise the very principles of justice and fairness.

These aren’t just numbers. These are lives derailed. Families broken. Communities destabilized. They represent a profound failure of systems that are meant to protect, and a perpetuation of historical injustices that continue to ripple through society.

Beyond policy and external perception, these erroneous narratives can profoundly impact internalized perception and the normalization of dangerous, unhealthy behaviors within marginalized communities and the broader society. A 2022 study in Demography titled "Outside the Skin": The Persistence of Black–White Disparities in U.S. Early-Life Mortality, highlights that while overall early-life mortality has declined, Black–White disparities remain stubbornly unchanged for preventable causes of death "outside the skin." Specifically, homicide mortality for Black males aged 15-24 is nearly 20 times higher than for White males in the same age group. This stark difference isn't solely due to individual choices but reflects racial differences in social exposures and environments, where persistent narratives of criminality can contribute to cycles of violence and trauma, often normalizing a sense of threat and vulnerability that takes a devastating toll on lives.

The Practitioner’s Responsibility

This is where you come in. Not as a savior, but as a steward. You are a gatekeeper of information, and with that comes a profound ethical obligation to ensure accuracy and context.

If you work in community violence prevention, in harm reduction, in schools, or in nonprofits, you hold influence. You speak on panels. You design curricula. You lead healing circles. You publish toolkits. And when you don’t interrogate the data you cite, or worse, repeat misinformation because it sounds aligned with your goals, you risk becoming complicit in the same systems you aim to disrupt. Your silence, or your uncritical repetition of flawed narratives, can unwittingly reinforce the very prejudices that lead to harm. The integrity of your work, and ultimately the well-being of the communities you serve, hinges on this commitment to truth.

We don’t need to shout down oppressors in every room. But we do need to speak clearly to each other. We need to hold one another accountable to the truth. We need to pause before citing that stat. We need to footnote our claims with context. And we need to say, out loud and often: “That’s not true. Here’s what the data actually shows.” This isn't about being confrontational for its own sake, but about fostering a culture of intellectual honesty and shared responsibility within our professional spaces. It's about building a foundation of factual integrity for all our efforts.

Not because we’re trying to win a debate. But because we’re trying to protect each other. Because when false narratives take root, they don't just harm individuals; they undermine the collective efforts to build a more just and equitable society for everyone.

What Do You Believe That You’ve Never Researched?

Data is not neutral. But it can be honest. If we let it. So I’ll end where I began: What do you believe that you’ve never researched? What story has shaped your worldview but never been cross-checked? And when that story shows up, on the news, in your work, in your mind, will you repeat it or re-examine it? Will you passively absorb information that reinforces existing biases, or will you actively engage with the evidence, even if it challenges your comfortable assumptions?

This reflection isn’t about guilt. It’s about growth. It’s about shedding the intellectual laziness that allows misinformation to thrive and embracing the diligent pursuit of understanding.

It’s about returning to the core of our practice: protecting life, honoring dignity, and building strategies rooted in truth, not assumption. It's about fostering a society where data is used as a tool for illumination and progress, rather than as a weapon for division and oppression.

Let’s stop letting bad data do the talking. Let’s be better stewards of the truth.